Artículo

Estudios en Seguridad y Defensa, 14(27), 91-114.

https://doi.org/10.25062/1900-8325.285

Strategy in the making: Russia-NATO Relations under Strategic Competition1

Estrategia en construcción: las relaciones entre Rusia y la OTAN en el marco de la competencia estratégica

Estratégia em elaboração: Relações Rússia-NATO sob Competição Estratégica

LUIS ALEXANDER MONTERO MONCADA2

MARÍA PAULA VELANDIA GARCÍA3

2 Magíster en Análisis de Problemas Políticos, Económicos e Internacionales Contemporáneos de la Universidad Externado de Colombia y el Instituto de Estudios Políticos de París, Francia. Magíster Honoris Causa en Inteligencia Estratégica en la Escuela de Inteligencia y Contrainteligencia del Ejército de Colombia “General de Brigada Ricardo Charry Solano”. Asesor de las Fuerzas Militares de Colombia en temas estratégicos y defensa nacional. Investigador del Departamento Ejército, de la Escuela Superior de Guerra “General Rafael Reyes Prieto”, Colombia. Contacto: luis. montero@esdegue.edu.co

3 Magíster en Estrategia y Geopolítica de la Escuela Superior de Guerra “General Rafael Reyes Prieto”, Colombia. Internacionalista de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Analista de medios para temas geopolíticos y consultora de revistas colombianas. Contacto: mariapaula2393@hotmail.com

Fecha de recepcion: 22 de enero de 2019

Fecha de aceptación: 4 de marzo de 2019

Abstract

In this article, we examine the elements that are being developed by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Russia in a strategic competition in Europe. Having analysed these elements, each sub-system, as described by the Realist Theory of International Relations, is facing major changes in today’s world politics. From Northern Europe to the Balkans and the Black Sea region, the analysis focuses on areas of tension that could potentially become problematic for the interaction between the two actors. Besides, the Baltic region is explained further due to its continuous activity regarding either hybrid or tradition war tactics. Finally, we draw a parallel between NATO, the EU and the USA as main actors in European Security and how the latter has been changing drastically since Donald Trump took office. We conclude by analysing potential risks, scenarios and conflicts between NATO and Russia in short range projections.

Keykords: NATO, Russia, Strategy, Europa, Military deployment, Realism.

Resumen

En este artículo se examinan los elementos que están desarrollando la OTAN y Rusia en el marco de una competencia estratégica en Europa. Una vez analizados estos elementos, cada subsistema, tal como lo describe la teoría realista de las relaciones internacionales, se enfrenta a importantes cambios en la política mundial actual. Desde el norte de Europa hasta los Balcanes y la región del Mar Negro, el análisis se centra en las áreas de tensión que podrían llegar a ser problemáticas para la interacción entre los dos actores. Además, la región del Báltico se explica con más detalle debido a su continua actividad en cuanto a tácticas de guerra híbrida o tradicional. Por último, se establece un paralelismo entre la OTAN, la UE y los Estados Unidos como actores principales de la seguridad europea y cómo esta última ha cambiado drásticamente desde que Donald Trump asumió el cargo. Concluimos analizando los posibles riesgos, escenarios y conflictos entre la OTAN y Rusia en proyecciones de corto alcance.

Palabras clave: OTAN, Rusia, Estrategia, Europa, Despliegue militar, Realismo.

Resumo

Este artigo examina os elementos que a OTAN e a Rússia estão desenvolvendo no âmbito de uma competição estratégica na Europa. Uma vez analisados estes elementos, cada subsistema, como descrito pela Teoria Realista das Relações Internacionais, enfrenta importantes mudanças na atual política mundial. Do norte da Europa aos Bálcãs e à região do Mar Negro, a análise se concentra em áreas de tensão que podem se tornar problemáticas para a interação entre os dois atores. Além disso, a região do Báltico é explicada com mais detalhes devido a sua atividade contínua em termos de táticas de guerra híbridas ou tradicionais. Finalmente, são traçados paralelos entre a OTAN, a UE e os Estados Unidos como principais atores da segurança europeia e como esta última mudou drasticamente desde que Donald Trump tomou posse. Concluímos analisando os riscos potenciais, cenários e conflitos entre a OTAN e a Rússia em projeções de curto prazo.

Palabras-chave: OTAN, Rússia, Estratégia, Europa, Desdobramento Militar, Realismo.

- Europe: The Chessboard

In the frame of realism, power, and the desire to accumulate it are the basic elements in the interaction between people, society, and politics. But since not all States can accumulate power on their own, the balance of power emerges as the only viable solution to avoid violence and direct confrontation (Morgenthau, 1962). But it is neo-realists who explain in depth what competition between actors is intended for: survival. Waltz (1979) would say that the International System is a group of actors interacting with each other in which competition to overcome the adversary is the final goal.

On the other hand, Henderson (1980) explains that competitive changes derived from strategy could occur in a short span of time, but could also involve several generations, if they occur naturally. Although the author analyses these changes from an economic point of view, in his analysis there are variables that can be applied to geopolitical strategic competition. Among these, Henderson (1980) cites the following elements:

the ability to understand the interactions between competitors as a complete dynamic system that includes their interactions.

the ability to make use of this knowledge to predict the consequences of a specific intervention in the aforementioned system as well as the new forms of stable dynamic equilibrium that will result from that intervention.

the availability of uncommitted resources that can be dedicated to different uses and purposes.

the ability to predict risk and performance with sufficient accuracy and confidence to justify the allocation of such resources.

the willingness to act decisively and commit those resources.

The use of these elements in the strategic competition between Russia and NATO in the Baltic region is reduced to the manipulation of available resources and skills to dispense with their hegemony in the region. Henderson (1980) adds that strategic competition revolves around making relevant changes in competitive relationships. In fact, the revolutionary quality is moderated only by two fundamental variables: 1) failure of the strategy can be as strong as its success; and 2) a defender on alert has a considerable advantage over the attacker.

With the end of the Cold War, capitalism in the hands of the United States was seen as the great winner of the confrontation between blocks, which was solidified by projects of integration between Western States such as the European Union (EU) and NATO. By 1991, Communism was no longer the main threat, but the West could not stop expanding due to an eventual breach with new emerging powers. Furthermore, four years later, the debates regarding the expansion of the NATO eastward oscillated between securing member States and posing a threat to Russia (Kugler, 1996). Securing States from a potential threat drove the NATO to faster expand its boundaries towards the East.

Figure 1. NATO Enlargement.

Source: Center for Strategic & International Studies (2017).

It is in 2008, at the Bucharest Summit, when the NATO officially embraces Georgia’s aspirations of being a member of the Organization. The elected government of Georgia had struggled with an autonomous district called South Ossetia, a region that is backed by Russia in its independentist aspirations and is considered an independent State by only few countries around the world. The timing for the eruption of the Russian - Georgian war in 2008 seems precise, in geopolitical terms. The addition of Georgia to NATO would imply a detention of Russia and its control of the regions which contain reserves of energetic resources or are necessary for Russia’s trade routes, as Alfred Mahan (1890) would put it. This is the true meaning, geopolitically, behind the Caucasus: it is the obligatory pass of pipelines from Central Asia to Europe.

This war opened the eyes of the West, and it was understood that Russia could no longer be fully trusted. But for realists it constituted an act of destabilization in the region, in the sense of showing the world that it was not the right time to include a country with an internal conflict into the world’s oldest military Alliance. Today Georgia’s aspirations are still on the table; NATO has not made a definite decision yet, and Georgia’s petition is discussed on each summit meeting (Brussels Summit Declaration, NATO, 2018b).

Talking about the Caucasus leads us to picture the Black Sea region. It is the continuation of the obligatory pass of pipelines from Central Asia to Europe, as mentioned before. This region, specifically, is distributed between either NATO member states (Turkey, Bulgaria and Romania), NATO partners (Ukraine and Georgia), and Russia. If there were a competition, Russia should be worried. But it is not before 2014 that Russia became an aggressive rival to the Organization. After the Orange Revolution, Russia saw a chance opening to obtain control over the long-lost seaport of Sevastopol and the Crimean Peninsula. With a 95% acceptance, on March 16, 2014, Crimea officially requested to be annexed to Russia.

After Russia’s officially annexing Crimea, the relations with NATO tensed and military build-up and political instruments started to play a definitive role in the interactions between these two actors. The fight over the Black Sea is not a fight Russia could easily win against NATO. Like in many other regions of Europe, Russia has been using its Sharp Power to destabilize countries located on the coasts of the Black Sea. As Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig (2017) describe it:

Contrary to some of the prevailing analysis, the influence wielded by Beijing and Moscow through initiatives in the spheres of media, culture, think tanks, and academia is not a “charm offensive,” as the author Joshua Kurlantzick termed it in his book Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power Is Transforming the World. Nor is it an effort to “share alternative ideas” or “broaden the debate”, as the editorial leadership at the Russian and Chinese state information outlets suggest about themselves. It is not principally about attraction or even persuasion; instead, it centres on distraction and manipulation (Ludwig & Walker, 2017).

It is an addition to the grand Russian strategy on the continent. How to balance an invisible war? That is a question that NATO has tried to answer and has been working on for years. In this region, NATO pays attention not only to Russia but also to their black sheep ally: Turkey. Even when Turkey is a Member State of the Organization, it has recently caused NATO some headaches. Ever since the 2016 failed coup d’état4, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has spoken roughly about the West’s support to Fethullah Gulen, the mastermind behind the coup, according to Turkey (Arango y Yeginsu, 2016). The event has driven the ally to move closer to Russia, politically, economically and militarily speaking. This approach has been a pain in the neck of the Alliance, because Turkey today grows closer to the East and drives away further from the West. The ultimate proof has been delivered at the door of NATO when Turkey refused to cancel the purchase of the missile defence system S-400. In tough declarations from the USA, it seems as if the NATO ally were moving further away from the West towards the East. Remaining a problematic member State Turkey has not cut short their commitment to the Alliance, though.

Turkey still cooperates with NATO through military exercises, defence spending and political instruments. However, there is a fissure within the Organization, which, in the eyes of Russia and under a perspective of Sharp Power, is a significant gain.

The Ukraine, on the other hand, is a matter that concerns both Russia and NATO. With the outcome of the Orange Revolution and the annexation of Crimea, Kiev is now in the eyes of NATO and the EU. Petro Poroshenko, President of the Ukraine, has expressed multiple times the Ukraine’s willingness to be part of both organizations. But with an internal conflict that resembles the South-Ossetia conflict, the fear that 2008 could be repeated lingers in the minds of NATO leaders. This does not mean, nonetheless, that countries like the United States had not supported the Ukraine politically and militarily. The West’s support for the Ukraine is imminent; but so is Russia’s current presence in the Donbass region. The ongoing conflict seems far from being resolved and it entails a security dilemma to the Alliance as to whether pursue expansion towards the Ukraine or avoid an increase of tensions with Russia.

With the fear of history repeating itself and the events in the Kerch Strait back in late 2018, the NATO has stepped up their aid to Ukraine by providing military equipment, deploying vessels and surveillance equipment to constantly monitor the Black Sea Region activity. This has led Russia to further increase missile exercises in Crimean territorial waters. From November 2018 until today, the Black Sea has seen the tensest relationship between the Alliance and Moscow.

Right where the Black Sea coasts end, starts the Balkan region. Out of eleven Balkan countries (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, Macedonia, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey and Romania), eight are member of NATO (Croatia, Montenegro, Albania, Macedonia, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey and Romania). Undoubtedly, this is a region under predominant influence of the Alliance. The Balkan territory is the land route from the Black Sea into the Mediterranean Sea. Unlike the rest of Europe, politically and in terms of security, the Balkans are very unstable. From car bombings over ethnic issues (Gall, 2001) to tensions between States, the Balkan region constitutes a conflictive factor to a European-style governance. Even when this reality may be conflictive to some ends, NATO is still receiving Balkan aspirations with Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina up next. Because of ethnic heritage issues, there are some situations to resolve for these two countries before being able to become full members.

Russia, however, consolidates an ally in the heart region that will help balance its influence: Serbia. The government of Belgrade has active communication and cooperation with Russia not allowing the country to feel left out. But the instability of the region has permitted Russia to penetrate it with its hybrid warfare strategies. In 2016, Montenegrin authorities accused the Russian government of plotting a coup d’état (Reuters, 2017).

According to Stojanovic (2018), Russia and the European Union have been competing for leadership in the Balkans. This competition has been driven by a discouragement of the countries in the region to be members of either NATO or the EU. But Russia’s strategy to expand anti-western sentiments is focused on Serbia. To develop such sentiments, Moscow has grown closer to Belgrade through military exercises (such as Zapad, Slavic Brotherhood) as well as through military, economic and political cooperation. Even when Serbia has called itself a neutral country, according to what Serbian Defence Minister Zoran Djordjevi said back in 2017, the clear closeness to Russia has shown neighbour countries that competition in the region is, in fact, very much alive (Sputnik, 2017).

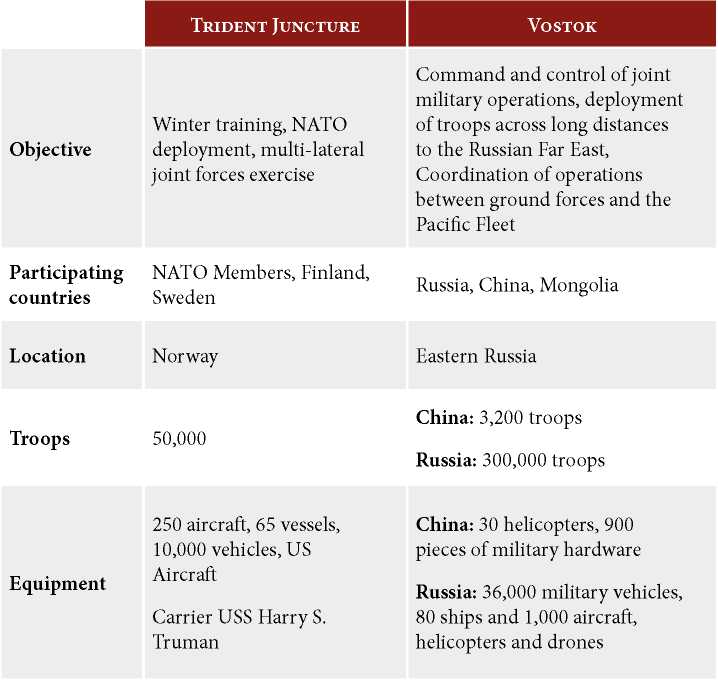

On the other hand, after the September military exercises performed by Russia in its Eastern region, Vostok 2018 became the largest display of power by Moscow since the Cold War. In the words of General Sergei Shoigu, the Russian Minister of Defence, the war games would be the biggest since a Soviet military exercise, Zapad-81 (West-81) in 1981, “In some ways they will repeat aspects of Zapad-81, but in other ways the scale will be bigger” (Osborn, 2018, parr. 7). In light of this display of hard power, NATO flexed its muscle for Trident Juncture that, in the words of Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg (NATO, 2018), is one of the Alliance’s “biggest exercises in many years”. In figures, both Vostok-18 and Trident Juncture played a crucial role in showing off capabilities and sent a specific message to the adversary.

Table 1. Trident Juncture-18 vs Vostok-18. 2018

Source: Personal creation based on NATO (2018), Woody (2018) and The Guardian (2018).

By comparison, both exercises demonstrate the military defence capacity of both sides. Altogether, the two exercises represent a scenario in which each block has to defend itself. But the defence mechanisms of NATO and Russia are very different. For example, Russia would have to mobilize a big number of troops and equipment in a short period of time, whereas NATO has different flanks supported by their members which would possibly allow for a quicker response. Defence and mobilization capacities were addressed in both exercises; but with the results being translated, Russia has shown that indeed it has the ability to move its troops faster in case there were a situation needing defence. This explains the amount of military equipment and troops used in the exercise, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Russia’s deterrence capacity in the Baltic (2017)

Source: Gramer (2017)

In terms of collective defence (apart from nuclear policy posture, cyber-security, etc.) NATO has got a different sort of territory to defend. Not as big an extension as Russia, but complicated due to the variety of members, projections of Russian force into the middle of that territory like Kaliningrad. In fact, not all of NATO’s flanks are standardized across that territory nor are their different armed forces used to working with each different from the big Russian force. This requires an extensive training exercise in order to assure effectiveness and swiftness in terms of reaction all over its Eastern Flank.

Additionally, the military spectrum does not only refer to these exercises. The tension arose as a consequence of the development of the Russian Novator 9M729 (NATO designation SSC-8). This Russian land-based cruise missile is believed to have a range between 500 km and 5,500 km breaching the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty conveyed by Russia and the United States to prevent further nuclear escalation. To put into perspective, the distance between Moscow and Lisbon amounts to around 4,700 km. The development of the aforementioned missile would be considered a threat to almost all NATO allies, depending on where the missile is deployed. These concerns have been voiced by NATO officials as well as US officials. Since the development is not official and Russia has denied breaking the INF Treaty, NATO’s alarms are beeping, and the system seems to be trembling.

Generally speaking, an overview of the strategic competition between Russia and NATO in Europe cannot be analysed without thinking of the Baltic. But before going deeper into how the strategic competition develops in this region, one has to examine the geopolitical importance of the Baltic Sea for both Russia and NATO. For Russia, the Baltic states have a large Russian-speaking population left over from the disintegration of the Soviet Union (USSR). Targeting Russian speakers has become important for Moscow through its Russkiy Mir (Russian Peace) policy.

In June 2007 President Putin signed a decree establishing the Russkiy Mir Foundation, for the purpose of “promoting the Russian language, as Russia’s national heritage and a significant aspect of Russian and world culture and supporting Russian language teaching programs abroad [...] The Foundation is a joint project of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Education and Science and supported by both public and private funds. The Russkiy Mir Foundation is headed by Vyacheslav Nikonov, Dean of History and Political Science at the International University in Moscow and founder of the Polity Foundation. The Foundation’s Board of Trustees consists of prominent Russian academics, cultural figures, and distinguished civil servants, and is chaired by Lyudmila Verbitskaya, Rector of St. Petersburg State University and Chair of the International Association of Russian Language and Literature Teachers (MAPRYAL) (Russian Government, 2017).

This policy has given Russia a reason to approach the Russian people living in the Baltic States more effectively, not only through language but also through what has been known as the passaportization (giving Russian speakers a Russian passport wherever they are near the motherland (Griegas, 2015). This strategy was also used for Ukrainian people who spoke and had ethnic, i.e. Russian, ties to the motherland, mostly in the eastern region: exactly where the conflict is still ongoing. Not only that; Russia has been using hybrid war to sow fear in the minds not only of the people but also of politicians (FINABEL, 2019). Worries about a possible new annexation of the Baltic States exist within the countries and that has driven NATO to flex a more powerful military muscle to aid their allies.

Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia are NATO members, which gives them a tool that protects them from any direct attack from Russia: Article 5 of the NATO treaty5. But how can you defend an ally from a non-armed attack? That is the question NATO has yet to answer and has been working on effortlessly since 2014. It is certain that the Alliance will not leave the Baltic States behind if anything happened. But it is still worrying that Russia can destabilize a whole region with hybrid warfare.

So how are NATO and Russia considering this competition in 2019? Four years after Crimea, tensions between the Organization and Moscow have not ceased. There are plenty of mechanisms that divert cooperation, and yet again, neo-realism strikes. It has become even more evident that someone has to deliver and secure both the Allies and the aspirations of the 29 governments. After last year’s NATO Summit in Brussels, Allies agreed that “Russia’s aggressive actions, including the threat and use of force to attain political goals, challenge the Alliance and are undermining Euro-Atlantic security and the rules-based international order” (Brussels Summit Declaration, NATO, 2018b). They agreed on reaching their defence spending goal, on rejecting Moscow’s annexation of Crimea as well as its political aspirations in European territory such as Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova while not leaving behind the NATO-Russia Council set to ease tensions. All the above under the flag of deterrence and collective defence.

Furthermore, competition between Russia and NATO is still palpable and tensions between these two actors continue increasing.

- NATO and Russia: In the Baltic

Competition between actors is manifest whenever these consider themselves rivals but not mortal enemies (Aron, 1985). This sort of confrontation is carried out as a possibility to demonstrate or impose power over the rival, framing it in a realist point of view. Many authors, in fact, explain the relationship between Russia and NATO as a rollercoaster where the annexation of Crimea was the lowest point. There has been a historic pattern that repeats itself over and over. It starts with a hopeful period, is followed by cooperation and projects that eventually end up in crisis and yet again it gets back to point one. It is a vicious circle that NATO and Russia have seen first-hand. In 1997, the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) was established followed by an improvement in the relations. Two years later, however, with the crisis in Kosovo, the circle came to its end and it had to start all over again (Presser, 2014).

The machinery of foreign policy and security derives from strategic culture. In this regard, NATO and Russia maintain different points of view on European security and what threatens it. The different perceptions of both parties about security must be considered in part taking into account that the strategic mind of each country relates to different security cultures (Padrtová, 2013). While Russia maintains an unwavering geopolitical understanding of security, NATO’s approach shifted away from the strictly geopolitical approach towards a broader interpretation of security. The real objective of NATO is to build trust among its partners. The Alliance is fostering a process of building trust through the gradual increase and expansion of daily contacts between NATO members and Russian officials because, in their opinion, it will help build a longer-lasting and reliable relationship (Padrtová, 2013). However, there are deep-rooted suspicions in some Russian circles and in several NATO countries, which deteriorate the intentions of both sides to cooperate.

“We do not consider that Russia is a threat to the NATO countries, the territory of NATO, and Russia should not consider NATO a threat to Russia” (Rasmussen, 2012). These statements were made before the annexation of Crimea in 2014, which changed the rhetoric of both the member countries and the heads of the Alliance (Padrtová, 2013). However, the Russian approach is different: The Kremlin perceives the Alliance as a military bloc hostile to its interests, as President Vladimir Putin put it clearly at the press conference following the meeting of the NATO-Russia Council in Bucharest, when he said that “NATO’s approach to borders threatens the security of the Russian Federation” (Padrtová, 2013).

Despite its fundamental criticisms, NATO defends the possibility of a political dialogue with Moscow. In April 2014, they decided to keep the channels open at the ambassador level. In fact, the lines of dialogue have also ended here, with the NRC calling only once since that date. Even more serious than the cessation of practical cooperation is the serious loss of confidence and the resurgence of traditional perceptions of threat, especially in certain countries of Central and Eastern Europe and in parts of the Russian leadership (Major & Klein, 2015).

However, after 2014 the tensions grew, and NATO and Russia were no longer partners. With an emotional speech in 2014 in Estonia, Lt. General Donald Campbell achieved an approach to those who felt unprotected after Russia’s actions in Crimea. His goal was to send a message in the sense that US troops would be in charge of the training of their Estonian counterparts, for an indefinite time. This would-be NATO’s response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine, which would later become a game of powers. A US deployment of F-16 fighter jets and Air Force personnel to Poland for training exercises, intensified aerial surveillance in the Baltic States and improved manoeuvres were the first pieces put into place on the western side of the chessboard (Granger, 2015). For the General of the American Air Force Phillip Breedlove, commander of the US European Command (EUCOM) and Supreme Allied Commander, the first moves were relatively simple but definitive.

A few weeks later, approximately 600 US paratroopers from the 173rd Airborne Brigade, based in Italy, were heading to Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia as part of what would later be called Operation Atlantic Resolve. According to Breedlove, a contingent the size of an airborne infantry company in each of the four countries would hardly be an obstacle against the “force of around 40,000” Russian troops concentrated on the Ukrainian border at that time, although that was not the main objective of the operation (Granger, 2015). The presence of American boots on the ground was the central tactical condition designed to signal the US commitment to the obligations of Article 5 of North Atlantic Treaty and the US Army would have no problems in getting to the fore.

Moscow, on the other hand, considers such movements as evidence of the aggressive and expansionist behaviour of NATO. In 2014 and 2015, it expanded military capacities in its Western Military District, which is next to the NATO members Norway, Poland and the Baltic States; the exercises were intensified, and weapons systems were modernized (Major & Klein, 2015). Russia also plans to strengthen its ground forces there and deploy more modern anti-aircraft systems. Additionally, Moscow uses demonstrations of military power as sabre rattling: the number of Russian aircraft flying near NATO airspace increased significantly over the past year, and the Kremlin’s nuclear threats also increased (Major & Klein, 2015). For instance, when in December 2014 and March 2015, short-range Iskander missiles with nuclear capacity were deployed in Kaliningrad for military exercises. What this means is the return of the security dilemma, which seemed overcome, in which the actions that one of the sides considers defensive are interpreted by the other as offensive, leading to an escalation.

Deterrent activities seek to influence the calculation and decisions of an adversary and, as such, try to influence the perceptions of the adversary. Once a State has defined its activities so that no third party may misunderstand them, what the adversary believes or thinks is all that can be offered (International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2017). Adverse perceptions are a function of three variables. The first is who the adversary is: his identity, values, fears and aspirations, goals and objectives, strategy and doctrine, and capacities. The second refers to the decision as to what influence and deterrence is desired: for example, whether they would use nuclear weapons. The third refers to the circumstances in which the decision is made (International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2017).

Therefore, it is understood that current deterrence theory is not based only on the number of nuclear weapons that a State may have. Today, the decisions in the Baltic region are taken considering the deployment of military equipment that each party performs and, consequently, their ability to react to them. In a report published by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, the increased deterrence of the North should be focused on command and control, air, land, sea and defence dialogue (Melino, Rathke y Conley, 2018). If this is considered, deterrence is understood as a mutual strategy to present mutual capacities in conflict scenarios. In this order of ideas, NATO (Figure 3) and Russia (Figure 2) begin to arm themselves in the region in such a way that for every deployment and military exercise there is an equivalent reaction or even, in many scenarios, a reaction on a higher scale.

Figure 3. NATO’s deterrence capacity in the Baltic (2017)

Source: Gramer (2017)

As immediate response mechanisms to possible threats, the military exercises are consolidated as a way of dissuasion by allowing the demonstration of the whole military apparatus. In the Military Balance report of 2017 by International Institute for Strategic Studies. (2017), a parallel is made between the exercises orchestrated by the countries by regions, where it can be seen that the Baltic region is one of the regions most involved in military training in the world. The following information shows the variation between the personnel used in each military exercise performed by Russia and NATO in almost two years. For the most part, it can be observed how Russia uses a greater number of personnel, possibly because of the ease of deploying troops throughout its nearby territories. Additionally, as described above, the new Russian security policy of 2016 seeks the use of a smaller number of more capable personnel in its armed forces.

In ongoing military exercises, NATO does not need the participation of the 29 Member States for the presence of the Alliance to be imminent. In the Baltic region in 2016, the member States of NATO carried out 16 military exercises the biggest and most ambitious of which were:

Spring Storm: It was organized in Lithuania in May, with the participation of Belgium, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, the United States and the United Kingdom. The goal was field work.

BALTOPS: Possibly the most important military exercise in the region, this inter-operational simulation was performed in the Baltic Sea with the participation of Belgium, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom and the United States. It employed 6,100 soldiers, 61 aircraft, 49 ships and 3 submarines.

Iron Wolf: With the participation of Denmark, France, Germany, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland and the United States, this exercise focused on field work and was carried out in Lithuania.

Anaconda: The largest exercise in the region, involved Albania, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Macedonia, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, United Kingdom and Ukraine. It was carried out in Poland and its objectives were cyber-security, field work, real-time exercises, among others.

Sabre Strike: This exercise was held in Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia with the participation of Canada, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the United States and the United Kingdom. The main objective was field training.

Trident Juncture: In this exercise the NATO participated, but it was not located in one specific place.

On the other hand, Russia also carried out approximately 10 exercises that caught the attention of both the press and the governments in this same year, among them:

CSTO Joint Exercise: Although this exercise was carried out in Tajikistan, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) becomes an option to demonstrate Russia’s leadership in security issues. The member countries of this organization who participated in the exercise were Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan.

Unbreakable Brotherhood: Once again with the member countries of the CSTO, the exercise was carried out in Belarus with a focus on peace-keeping forces.

Zapad: The most ambitious war games in Russia that involved approximately 12,000 troops and was held in Belarus and Kaliningrad. This exercise was carried out in response to a possible scenario of “invasion” of States outside Belarus or Russia in any context.

Common security challenges require unified responses, so cooperation between NATO and Russia is necessary to ensure the security of the Euro-Atlantic zone. Both Russia and NATO should deepen mutual cooperation where there are common interests and ice differences in areas of conflict, which allows us to approach strategic competition according to Henderson (Henderson, 1980). This idealist thought is relegated by a competition derived from a new Cold War in the Baltic region. It becomes a game of deterrence where the deployment of equipment represents an imminent threat to the adversary. Therefore, in the region exercises of great magnitude are carried out as was Zapad, but Russia is not left alone to seek the alliance and leadership of organizations such as the CSTO to counteract the power that NATO represents.

Additionally, it seeks strategic alliances with other countries to demonstrate its capacity as a main actor in a regional system. For example, in July 2017, Russia and China held their first joint military exercise in the Baltic Sea (Higgins, 2017) demonstrating Russia’s willingness to establish alliances that will allow it to project its power and guarantee its allies protection capacity in scenarios of aggression on the part of the adversary.

- Russia, the European Union and the United States: A balance for security and defence.

Certainly, the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) has been consolidated, historically, as one of the main pillars in spite of having being one of the greatest challenges for the European Union; and this pillar specifically transcends the inner “boundaries” of the Union and the domestic issues while it tries to deal simultaneously with a number of transnational/global elements that allow the Union to establish an efficient policy to respond the actual security challenges.

One of these elements, undoubtedly, is the configuration of geostrategic alliances that benefit not only the fulfilment or application of the internal security policies but also allow the development of cooperation in international scenarios. Consequently, it is possible to evidence how, due to the passing years, the EU has thrown on the table the importance of developing relations with foreign States that support Brussels (Council of the European Union, 2018).

It is clear that in order to accomplish the goals mentioned before and in line with the configuration of the International System, the EU has been looking for support and bonds with strategic countries where crises haves been manifest or sustained. Explaining the more than thirty missions of the CSDP since 2003, divided between civil or operational missions while it seeks to maintain close and balanced relations with important States such as the United States and Russia.

Faced with this supposedly balanced relationship when analysing the actions taken by the European Union, it is clear that the balance tends to position itself directly towards the United States, as evidenced by the Bratislava summit in September 2016. There, the EU leaders decided to give a new impetus to European external security and defence by strengthening EU cooperation in this area. In fulfilment of this commitment, in December 2016 the leaders adopted the implementation plan in the field of security and defence that celebrated the proposal of the European Commission on the European Defence Action Plan and urged the rapid adoption of measures to increase cooperation between the EU and NATO.

This was maintained in the Treaty of Lisbon where it was ensured that the group of member States can strengthen their cooperation in defence issues by establishing a permanent structured cooperation with non-member States. On June 22, 2017, the EU leaders agreed to launch the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in order to strengthen the security and defence of Europe and on December 11, 2017, the Council established the corresponding guideline. All EU member States participate in it, with the exception of three countries (Denmark, Malta and the United Kingdom) and approved an initial list of 17 projects to be undertaken under the PESCO that cover, among others, the following areas: training, capacity development, operational availability in terms of defence in the constant company of NATO and the United States.

On June 25, 2018, the Council adopted governance standards for projects within the framework of the PESCO and updated the list of projects and their participants, including a second round of projects that was scheduled for November 2018 with the participation of all of the representatives of the United States and a delegate from NATO (Council of the European Union, 2018).

From this perspective, the EU and NATO cooperate in a declaration made on July 10, 2018 (NATO, 2018c), which constitutes a shared vision of how the EU and NATO will act jointly in the face of threats to common security, focusing their cooperation on areas such as military mobility, cyber-security, hybrid threats, the fight against terrorism, women, and security. The new joint statement stresses that recent EU efforts to strengthen cooperation in security and defence reinforce transatlantic security:

We welcome the EU’s efforts to strengthen European security and defence to better protect the Union and its citizens and promote peace and stability in neighbouring countries and in other regions. The Permanent Structured Cooperation and the European Defence Fund contribute to these objectives.

The previous statement is based on the objectives of the previous joint statement of July 2016. The latter was aimed at strengthening cooperation in seven strategic areas, namely hybrid threats, operational cooperation, including maritime issues, cyber-security, defence capabilities, industry, and research, coordinated manoeuvres, and capacity building.

These types of institutional alliances and commitments allow us to dimension the close relationship between both international agents based on what happens with respect to the traditional relationship between the European institutions and the Russian State; as an example, we can see how since 2003 the mention of Russia is very generic in the European Security Strategy (ESS), where it is considered “an important speaker” in relation to world problems. In this way it is evident that from that moment until the last declarations issued in 2018 the EU must continue to engage “in the strengthening of our relations with Russia, a factor of consideration for our security and prosperity. Respect for our common values will move us more resolutely towards a strategic partnership” (Nieto, 2016).

The EU and Russia had agreed to strengthen their cooperation with the creation of four common spaces: the economic space; the area of freedom, security and justice; the external security space, including non-proliferation and crisis management; and the space of research and education in the framework of the ACC. The summit of the EU and Russia held in Moscow in May 2005 established the instruments for the development of these four spaces. But in 2007 Russia suspended the application of the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) that had been considered the pivotal point of the new European security architecture (Nieto, 2016).

Therefore, in spite of the institutional dynamics that show a trend towards the West, it is now possible to see how individual countries like France or Germany have openly promoted the need for an approach to the Russian State in this specific field. At the beginning of this year, through an official statement Emmanuel Macron made it known to his peers that “Europe can no longer count on the United States for military protection” and proposed a “new project to reinforce solidarity in Europe and reorder its architecture weaving in turn new strategic alliances with such decisive actors as Russia and Turkey to face the new threats of the world order” [author translation] (Juez, 2018, párr. 3), statements that have been widely supported by Angela Merkel, especially after the decision of the new North American government to withdraw from the nuclear agreement with Iran.

Precisely a new stage can be seen in the decisions made by Serbia. The Serbian interest to enter the European Union is well known, which would imply a partner in a strategic region to face threats such as illegal migration as well as human and drug trafficking. However, the military proximity between Serbia and Russia is also well known, so that the Balkan State can serve as a pivot to the Russian interests of rapprochement with Europe. The closeness between Serbia and Russia was recently celebrated by both heads of State in a ceremony that reminded the West that NATO is not part of the plans for the Balkan country.

I told Putin that we have good relations with all military alliances, including NATO. But Serbia has no striving and no plans to be part of NATO. Serbia wants to safeguard its military neutrality and that is why we are taking effort to strengthen our army to be able to repel any possible attacks on our country said by Alexander Vucic (TASS, 2018).

But questionably enough, NATO and Serbia participated in a military disaster-response exercise that, oddly enough, has not worried Moscow as much as was expected. One would have to question if we could consider Serbia as Russia’s “Trojan Horse” to NATO.

In this aspect, the actions undertaken by the current US government under Donald Trump on issues such as economic guidelines and energy issues explain to a large extent the decision of European States to begin a rapprochement with the Russian government. Declarations made by Trump in reference to the European Union as its “foe” only reiterate the real consequences of the decisions exercised as pressure by the US government, as it was at the time the abandonment of the Paris agreement, the breakdown of the nuclear agreement, the implementation of the “First Energy Plan” energy plan that has meant a significant commercial competition not only with the EU, but also with the same countries of the North Atlantic Treaty and China.

Conclusion

Under a general point of view, NATO and Russia have grown further apart even though the political mechanisms had been created to continue the dialogue. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 marks a point of inflection where frictions increased and both parts stepped up their deterrence capacities in order to either continue their hybrid activities (Russia) or prevent the enlargement of a breach in that matter (NATO). This is not only a matter in Ukraine but also all of the regions within the big system which is Europe (Balkan, Baltic, Northern, Eastern and Mediterranean).

It is the strategic competition that explains that frenemy6 relation between NATO and Russia. We can see how the interaction between the competitors in the system and the understanding of this gives us tools to predict the consequences of these scenarios. On the other hand, the resources in the region (from the economic ones to even social ones) are destined to a specific purpose for both competitors. For example, the Russky Mir policy (which seeks to reach out to Russians in other territories) can be seen as a foreign policy resource for Russia.

In the frenemy relation, as the first element, we note the interaction of the actors in the system so that events such as the NATO-Russia Council and the different meetings on surveillance and military exercises show that the interaction between them is active. The accessibility to resources and the synergy between NATO and Russia allow the prediction of a conflict scenario between both parties to constitute a total annihilation of both opponents. This is why deterrence is determined as a final tool that defines strategic competence between the parties.

In a parallel drawn about NATO’s and Russia’s biggest exercise in years, Trident Juncture and Vostok send a political message to both parties. On the one hand, NATO is now trained to defend its coldest flanks, no longer leaving Russia the advantage it once had. Aside from hybrid war, NATO is committed to a greater, more effective synergy between its members and allied countries. Coordination between highly trained armies (such as the United States) and smaller armies allow the collective defence principle to work slightly better.

The political message of the deployment of the USS Harry S. Truman most definitely pretends to show US commitment in these times of uncertainty under the Trump Administration.

Vostok, however, showed Russia’s military growth since the fall of the USSR. Having fewer participants and, in fact, opponents allowed the focus of the exercise to be the capacity of deploying a bigger number of troops faster and more effectively. It also demonstrated the necessity of the coordination with the Pacific Fleet denoting a new geopolitical sphere surging in today’s military challenges.

Although both exercises intended to strengthen a defensive principle on the side of both parties, Russia’s military exercise did seem to have a bigger and more effective impact on Western countries. This means that in terms of competition, Russia may have won due to the fact that NATO exercise seemed huge but unlikely to improve any capacity.

On the other hand, we can see that tension flanks between NATO and Russia in the Baltic are not relegated only to highly trained military apparatus to guarantee mutual destruction. The war takes already place in strategies that are hardly visible to the common eye and are based on misinformation to sow uncertainty in the eyes of the adverse population. With the evolution of wars and developments in international law, direct conflicts between States are increasingly distant. Even so, the struggle for the consolidation of a hegemony at regional levels continues, which provokes tensions between the actors. That is why we understand that the projection of strategic competence in the Baltic region is based on deterrence generated by hard power represented in military deployments, military exercises, missile deployment and economic sanctions; plus the soft power represented by appealing to culture in external territories and the diplomatic efforts between the parties; and, finally, the sharp power represented in the campaign of disinformation, propaganda and cyberattacks among the actors to delegitimize the actions of the other. The sum of these three powers makes a strategic policy that balances power in a highly important region.

Although the European Union has traditionally moved between self-defence architecture - but with serious problems stemming from community distances and disparities in the State security agendas - and the strategic alliance with NATO, it is possible to observe a trend to build bridges towards Russia as a potential future ally, with which a shared energy agenda that requires less costs than the transatlantic dialogue. Projects like South Stream and North Stream II provide evidence that even when these energy blueprints are debated and questioned by some member States, countries like Germany and Turkey perceive greater benefits by maintaining positive and constructive relations with Russia rather than alienating this country. This does not mean, however, that sanctions will be lifted easily; but it does illustrate the spectrum of how member States start to oscillate away from Washington.

This closeness would necessarily imply a fundamental re-arrangement in the projection of US power on the Eurasian chessboard, as well as the change in the balance of forces that imply issues such as the sovereignty of the Baltic States and even the relationship between the Union European Union and the United Kingdom. On the one hand, the United States would lose decisive influence in one of the most important geostrategic areas at the global level by opening more spaces of action to Moscow, affecting European support for operations in the Middle East and Central Asia. Secondly, possibly the Baltic States would have to renegotiate their margin of manoeuvre in relation to Russia, yielding part of their sovereignty to the Moscow agenda; this does not imply, however, that they are being eliminated from the map. Finally, it would be the ideal scenario where the political and now defence gap were extended to oblige, on the one hand, the United Kingdom close to the US and, on the other hand, the European Union hypothetically close bilaterally to a Russian agenda to take divergent paths.

1 Artículo de reflexión ligado al proyecto: “El tridente del poder estratégico. Inteligencia, Operaciones Especiales y poder ciber en el siglo XXI” que hace parte la línea de investigación “Estrategia, geopolítica y seguridad hemisférica” perteneciente al grupo de investigación Centro de Gravedad, reconocido y categorizado en A por Colciencias con el código COL0104976, vinculado al Departamento Ejército, adscrito y financiado por la Escuela Superior de Guerra “General Rafael Reyes Prieto”, Colombia.

4 According to the Cambridge Dictionary (2018) a “sudden defeat of a government through illegal force by a small group, often a military one”.

5 “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defense recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall immediately be reported to the Security Council. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security” (NATO, 2018a).

6 According to the Cambridge dictionary (2018), a person who pretends to be your friend but is in fact an enemy.

References

Arango, T. y Yeginsu, C. (2016). Turks Can Agree on One Thing: U.S. Was Behind Failed Coup. The Ney York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/03/world/europe/turkey-coup-erdogan-fethullah-gulen-united-states.html

Aron, R. (1985). Chapter 5. In Aron, R. Peace and War: A Theory of International Relations. Rotledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Cambridge Diccionary. (2018). Retrieved from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/coup-d-etat

Center for Strategic & International Studies. (2017). NATO Enlargement. Retrieved from https://medium.com/center-for-strategic-and-international-studies/nato-enlargement-a-case-study-c380545dd38d

Consejo de la Unión Europea. (2018). Cooperación de la UE en materia de seguridad y defensa. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/es/policies/defence-security/

Finabel. (2019). Finabel European Army Interoperability Centre. In The Baltic’s response to Russia’s Threat - How Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania reacted to the recent actions of the Russian federation Retrieved from https://finabel.org/the-baltics-response-to-russias-threat-how-estonia-latvia-and-lithuania-reacted-to-the-recent-actions-of-the-russian-federation/

Gall, C. (2001). Bomb Kills 7 Serbs In Kosovo Convoy Guarded by NATO. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2001/02/17/world/bomb-kills-7-serbs-in-kosovo-convoy-guarded-by-nato.html

Gramer, R. (2017). This Interactive Map Shows the High Stakes Missile Stand-Off Between NATO and Russia. Foreign policy. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/01/12/nato-russia-missile-defense-stand-off-deterrence-anti-access-ar-ea-denial/

Granger, J. (2015). Operation Atlantic Resolve A Case Study in Efective Communication Strategy. Military Review. Retrieved from https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/MilitaryReview_20150228_art019.pdf

Griegas, A. (2015). NATO’s Achilles Heel: The Baltic States. In Griegas, A. Beyond Crimea: The New Russian Empire (pp. 136-172). New Haven: Yale Press. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300214505.003.0005

Henderson, B. D. (1980). Strategic and natural competition. The Boston Consulting Group.

Higgins, A. (2017). China and Russia Hold First Joint Naval Drill in the Baltic Sea. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/25/world/eu-rope/china-russia-baltic-navy-exercises.html

International Institute for Strategic Studies. (2017). The Military Balance. International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Juez, B. (2018). Macron aboga por incluir a Rusia en la nueva defensa europea. El Mundo. Retrieved from https://www.elmundo.es/internacional/2018/08/28/5b843437ca-474120628b463a.html

Kugler, R. L. (1996). Enlarging NATO: The Russian factor. Santa Mónica: Rand Corporation.

Ludwig, J. & Walker, C. (2017). The Meaning of Sharp Power: How Authoritarian States Project Influence. Foreign Affairs.

Mahan, A. (1890). Strategic competition and natural competition.

Major, C. & Klein, M. (2015). Perspectives for NATO-Russia Relations. Berlin: German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

Melino, M., Rathke, J. & Conley, H. A. (2018). Enhanced Deterrence in the North. Nueva York: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Morgenthau, H. J. (1962). Politics in the Twentieh Century, vol. I, The decline of democratic politics. Chicago: University of Chicago.

NATO. (2018). Trident Juncture 2018. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/na-tohq/157833.htm

NATO. (2018a). The North Atlantic Treaty, 4 April 1949. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/ie/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm

NATO. (2018b). Brussels Summit Declaration. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_156624.htm

NATO. (2018c). NATO and EU leaders sign joint declaration. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_156759.htm?selectedLocale=en

Nieto, M. I. (2015). Russia and the global security strategy of the European Union. UNISCI Discussion Papers 2016, 197-216.

Osborn, A. (2018). Russia to hold its biggest war games since fall of Soviet Union. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-wargames/russia-to-hold-its-biggest-war-games-since-fall-of-soviet-union-idUSKCN1LD0OP

Padrtová, B. (2013). Russia-NATO Relations. Centre for European and North Atlantic Affairs.

Presser, S. (2014). NATO and Russia: Geopolitical Competition or Pragmatic Partnership? Praga: Association for International Affairs.

Rasmussen, A. (2012). Statement by NATO Secretary General at the press point following the NATO-Russia Council meeting in Foreign Ministers session, 19 April 2012. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/opinions_86234.htm

Reuters. (2017). Montenegro begins trial of alleged pro-Russian coup plotters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-montenegro-election-trial/montenegro-begins-trial-of-alleged-pro-russian-coup-plotters-idUSKBN1A413F

Russian Government. (2017). Russkiy Mir Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.russ-kiymir.ru/languages/spain/index.htm

Sputnik. (2017). Serbia ‘Remains Military Neutral State’ Despite Montenegro’s NATO Bid. Retrieved from https://sputniknews.com/military/201704261053005868-serbia-montenegro-nato-djordjevic/

Stojanovic, D. (2018). EU and Russia battle for influence in Balkan region. The independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/eu-brussels-russia-moscow-kremlin-balkans-ukraine-jean-clauder-juncker-vladi-mir-putin-nato-latest-a8226786.html

TASS. (2018). Serbia doesn’t want to be part of NATO, Vucic says. Retrieved from https://tass.com/world/1023988

The Guardian. (2018). Russia begins its largest ever military exercise with 300,000 soldiers. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/11/russia-largest-ever-military-exercise-300000-soldiers-china

Vargas Hernández, J. G. (2009). El Realismo y el neorealismo estructural. Estudios Políticos Vol. 9(16). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.24484903e.2009.0.18777

Waltz, K. (1979). Theory of International Politics. McGraw Hill.

Woody, C. (2018). Russia is getting ready for war games with 300,000 troops — but the size isn’t the only ‘unprecedented’ thing about it. Business insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/russian-vostok-18-war-games-will-include-china-for-the-first-time-2018-8s

Nieto, M. I. (2015). Russia and the global security strategy of the European Union. UNISCI Discussion Papers 2016, 197-216.

Osborn, A. (2018). Russia to hold its biggest war games since fall of Soviet Union. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-wargames/russia-to-hold-its-biggest-war-games-since-fall-of-soviet-union-idUSKCN1LD0OP

Padrtová, B. (2013). Russia-NATO Relations. Centre for European and North Atlantic Affairs.

Presser, S. (2014). NATO and Russia: Geopolitical Competition or Pragmatic Partnership? Praga: Association for International Affairs.

Rasmussen, A. (2012). Statement by NATO Secretary General at the press point following the NATO-Russia Council meeting in Foreign Ministers session, 19 April 2012. Retrieved from https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/opinions_86234.htm

Reuters. (2017). Montenegro begins trial of alleged pro-Russian coup plotters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-montenegro-election-trial/montenegro-begins-trial-of-alleged-pro-russian-coup-plotters-idUSKBN1A413F

Russian Government. (2017). Russkiy Mir Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.russ-kiymir.ru/languages/spain/index.htm

Sputnik. (2017). Serbia ‘Remains Military Neutral State’ Despite Montenegro’s NATO Bid. Retrieved from https://sputniknews.com/military/201704261053005868-serbia-montenegro-nato-djordjevic/

Stojanovic, D. (2018). EU and Russia battle for influence in Balkan region. The independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/eu-brussels-russia-moscow-kremlin-balkans-ukraine-jean-clauder-juncker-vladi-mir-putin-nato-latest-a8226786.html

TASS. (2018). Serbia doesn’t want to be part of NATO, Vucic says. Retrieved from https://tass.com/world/1023988

The Guardian. (2018). Russia begins its largest ever military exercise with 300,000 soldiers. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/11/russia-largest-ever-military-exercise-300000-soldiers-china

Vargas Hernández, J. G. (2009). El Realismo y el neorealismo estructural. Estudios Políticos Vol. 9(16). Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.24484903e.2009.0.18777

Waltz, K. (1979). Theory of International Politics. McGraw Hill.

Woody, C. (2018). Russia is getting ready for war games with 300,000 troops — but the size isn’t the only ‘unprecedented’ thing about it. Business insider. Retrieved from https://www.businessinsider.com/russian-vostok-18-war-games-will-include-china-for-the-first-time-2018-8